Billy Elliot the Musical – History and Context

Glossary of Terms

Bairn: child

Bonny Lad: informal term of endearment or form of address

- Bonny: attractive/healthy

- Lad: boy

Bugger off: get lost, go away

Co-op: a chain of food stores commonly owned by their customers. Purveyor of pasties.

Cush: nice, good, excellent

Gagging for: (slang) to have an extreme desire for something.

Geordie: someone from Newcastle upon Tyne.

Geordie: someone from Newcastle upon Tyne.

Howay: come on!, come along, or hurry up

Mank: not nice, unpleasant, disgusting

Nowt: nothing

Pasty: a popular British pie. Often filled with meat and potato.

Please yer Bessie: suit yourself

Scab: a worker who acts against the trade union policies, especially strikebreakers.

That’s your pigeon: that’s your business

The Creation of Billy Elliot the Musical

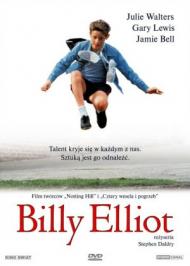

Billy Elliot the Musical is based on the 2000 movie, Billy Elliot, written by Lee Hall who drew much of the story from his experiences growing up in Newcastle in the 1970s and 1980s and finding a passion for the arts.

Billy Elliot the Musical is based on the 2000 movie, Billy Elliot, written by Lee Hall who drew much of the story from his experiences growing up in Newcastle in the 1970s and 1980s and finding a passion for the arts.

“It’s a sort of fantasy autobiography. None of it is literally true. All of it is emotionally true.” — Lee Hall

Lee Hall’s ballet was literature and his Royal Ballet School was Cambridge University. Hall was expected to follow in his father’s footsteps and work alongside him. Stepping outside that box of the familiar was largely unprecedented and when Hall discovered his love for reading and writing it was often met with fear and resistance, even from family.

“I think [my parents] just thought there was no way somebody from this background is ever going to be able to do it as a writer.” — Lee Hall

Billy Elliot the Musical follows Billy Elliot against the backdrop of the year long 1984/85 miners’ strike that threatened entire communities like Newcastle where unions like the NUM dominated. When the 1984/85 miners’ strike broke out it became such a vivid part of Lee Hall’s childhood. The strike was such a clear memory of two vastly different worlds clashing and erupting into literal battles on everyone’s doorsteps, it became an obvious frame in which to place the story of Billy Elliot.

“In a way it’s an example of art, of something beautiful coming out of something so tragic . . . If you have art, it can ease the pain of any terrible situation” — Elton John

Elton John saw the film when it premiered at Cannes and he had to be dragged from the theatre sobbing because he related so deeply to Billy Elliot’s story.

“The story is very similar to mine: Trying to be something out of the ordinary. Having a talent and wanting to break free from what your parents want you to do.” — Elton John

Elton John quickly approached Hall with the concept of turning his film into a musical. Hall couldn’t imagine it. He had always seen Billy Elliot’s story as a film and he couldn’t reconcile the idea of dancing miners with the depth of the story he created. Originally, Hall thought the idea was “rubbish” but he had to meet with him because “he’s Elton John.” Soon, however, he saw the connection John had with the story and the emotional impact musical theatre can offer and they created the musical adaptation, allowing it to take its own shape while keeping the heart of the film. When the film was created in 2000 the profession of deep mining, though incredibly depleted in the fifteen years since the strike had ended, still existed. By the time the play premiered in 2005 deep mining in Britain had all but ended. This change helped strengthen and clarify the themes of loss in Billy Elliot and influenced the adaptation to allow more of the focus to be placed on the miners and the miners’ strike alongside the major focus on Billy.

Elton John quickly approached Hall with the concept of turning his film into a musical. Hall couldn’t imagine it. He had always seen Billy Elliot’s story as a film and he couldn’t reconcile the idea of dancing miners with the depth of the story he created. Originally, Hall thought the idea was “rubbish” but he had to meet with him because “he’s Elton John.” Soon, however, he saw the connection John had with the story and the emotional impact musical theatre can offer and they created the musical adaptation, allowing it to take its own shape while keeping the heart of the film. When the film was created in 2000 the profession of deep mining, though incredibly depleted in the fifteen years since the strike had ended, still existed. By the time the play premiered in 2005 deep mining in Britain had all but ended. This change helped strengthen and clarify the themes of loss in Billy Elliot and influenced the adaptation to allow more of the focus to be placed on the miners and the miners’ strike alongside the major focus on Billy.

Mining and Mining Communities

Many pit villages owed their existence to coal and mining was the focus for the whole community. Mining was difficult and dangerous work and mining communities were very aware of the price they paid, in terms of damaged and destroyed bodies, for producing coal.

Many pit villages owed their existence to coal and mining was the focus for the whole community. Mining was difficult and dangerous work and mining communities were very aware of the price they paid, in terms of damaged and destroyed bodies, for producing coal.

“I enjoyed being a miner . . . because of the camaraderie you had . . . Given the environment you worked in if you didn’t laugh you would have cried.”

Miners usually worked at least 12-hour shifts deep within the mines cutting coal or moving cut coal to conveyers that would take it to the pit’s mouth. Some of these mines would be soaking wet. Others, especially deep pits (sinking as deep as 1,000 feet), were unbearably hot. Some miners would have to travel deep within the mines to cut coal, sometimes under roofs that were no more than three feet high.

Mining took a heavy toll on the body with lots of disabled older miners and many deaths. Between the 1950s and 1960s more than 1,000 miners were officially recorded as dying each year from pneumoconiosis. Respiratory illnesses were the biggest long-term health danger in mining, and in different communities and at different times, it was known as miners’ asthma, miners’ lung, black lung, black spit, the dust, and diffuganal (Welsh for shortness of breath).

“When the deaths and the injuries are spread out over the weeks and months and are scattered among the collieries in various coal-fields they tend to be ignored. It is only when there is a disaster that people suddenly become aware of the hazardous nature of mining, and even then it becomes a ten-day wonder until the next time.”

Throughout British mining history there were hazards and dangers everywhere from explosions, fires, and roof falls, to suffocating gasses and flooding. Miners would often be given a token for identification before going underground in case of an accident. At the height of the industry in the 1920s, 1.2 million men were employed in the pits and approximately 2,000 died every year in accidents. In 1909 a devastating blast at the West Stanley pit shook the whole mine and killed 160 miners. 59 of the victims were under the age of 20.

However, many miners appeared unfazed by the risks associated with coal mining, the dangers offset by economic opportunities. These shared hardships and dangers also helped unify mining communities. Nearly everyone in these communities voted for the Labour party, was part of a union, and shared a political understanding of self-help and community protection built around their shared unions. This culture clashed with a rapidly growing service economy focused on ramped up consumerism and individualism that was developing in 1980s London. These close-knit communities helped miners survive without money, food, and electricity during the strike as everything that could be repossessed was.

The NUM and Margaret Thatcher

“A man [has a] right to work as he will, to spend what he earns, to own property, to have the state as servant and not as master.” — Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Thatcher was elected as the first female Prime Minister of Britain in 1979. She was politically opposed to state-owned industry and determined to crush the unions. Thatcher referred to the unions as “the enemy within” and union strikes as the “British disease.” When the strike began in 1984, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) was one of the most powerful unions in Britain and Thatcher knew breaking the NUM would clear the way for taking down other unions.

Margaret Thatcher was elected as the first female Prime Minister of Britain in 1979. She was politically opposed to state-owned industry and determined to crush the unions. Thatcher referred to the unions as “the enemy within” and union strikes as the “British disease.” When the strike began in 1984, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) was one of the most powerful unions in Britain and Thatcher knew breaking the NUM would clear the way for taking down other unions.

Between WWI and WWII, the mines’ working conditions had deteriorated and miners’ wage levels and their trade unions were under attack. This provided the backdrop for a period of embittered relations between capital and labor. During the 1920s there were several miners’ strikes. However, they were not often successful as pit owners controlled many of the colliery houses that miners lived in and, during strikes, they would put miners and their families out on the street. In 1926 the miners were starved back to work. Conditions improved when the coal industry was nationalized in 1947, taking the coal industry from privately-owned to government-owned, and the NUM was formed and remained one of the most powerful unions until the 1984/85 strike.

Following nationalization, the NUM had gone on strike in 1972 and 1974 over wages. Both were highly successful for the miners and increased their pay. In 1974, Prime Minister Edward Heath declared a state of emergency and instituted a three-day work week for the duration of the strike because of the need to conserve energy. Heath hoped this would lead to public backlash against the miners. However, he government took the brunt of the criticism and Heath and his Conservative/Tory party were voted out of office while the Labour party and the miners’ union both flourished.

Thatcher put Ridley’s ideas into effect when planning to take on the NUM and, in preparation, bought and stocked foreign coal and equipped a large, mobile squad of police ready to employ riot tactics at picket lines. The foreign coal ensured that individuals outside of mining towns would not experience the effects of the miners’ strike in terms of limited coal supplies and, therefore, limited power.

On March 5, 1984, the NUM went on strike in response to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s plan to close pits, a plan that would lead to the loss of thousands of mining jobs.

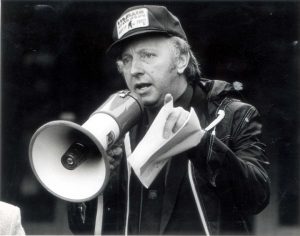

Arthur Scargill

“Our Union has consistently pledged itself to fight against pit closures and reductions in manpower levels, while at the same time demanding decent wages and conditions for British miners.”— Arthur Scargill, NUM President from 1982 to 2002

The Cortonwood Colliery in Yorkshire was one of the first mines scheduled to close and, when the miners working there walked out in protest on March 5, NUM executives called on other areas to support them. After individual regions chose to join the strike, Arthur Scargill took the protest nationwide. However, Scargill failed to put the decision to strike to a national ballot/union vote. So, many miners not facing imminent pit closure chose to keep working.

”I want to say to all those men that are still at work: no matter what arguments you put forward, you cannot ignore the most important and precious trade union principle upon which the strength of our movement has been built. When workers are in dispute, you do not cross picket lines.” — Arthur Scargill

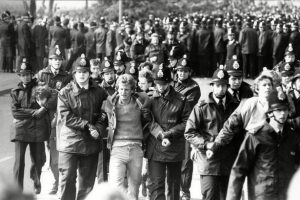

Miners who continued to work during the strike, also called scabs, were seen by strikers as betraying their union and their fellow miners and aiding in the destruction of their industry. Division within the NUM led to divisions within communities as well as anger and hatred that lasted long after the strike ended. These divisions also created flying pickets. Striking miners would travel to Nottinghamshire where miners were refusing to go on strike to picket and try to prevent miners from going to work. Police officers would be at the pits before dawn, before the striking miners arrived and would escort miners who continued to work, or ‘scabs,’ past the picket lines and into the mines.

Women in the Strike

Mining communities often had strict gender roles with ideas of ‘manhood’ and ‘manliness’ that permeated these communities. Boys followed their fathers into the mine. They were fearless. They played sports. They didn’t engage in the arts.

Mining communities often had strict gender roles with ideas of ‘manhood’ and ‘manliness’ that permeated these communities. Boys followed their fathers into the mine. They were fearless. They played sports. They didn’t engage in the arts.

Meanwhile, women were banned by law from working underground in the mines and in mining towns women were often relegated to positions in the home to the roles of wife and mother. During the strike, women upended gender expectations by forming Women Against Pit Closures and actively taking part in the strike.

“Men thought we were content with our lot. Now they realise that a woman is not just a wife in the house.” — Barbara Williams, WAPC Member

After the strike began, a group of women got together in Barnsley and formed Women Against Pit Closures (WAPC). Soon after, individual groups of women all over the country set up their own spontaneous action groups under the WAPC name. Many women involved had fathers, sons, brothers, etc. who were miners while others just felt strongly about the miners’ cause. On May 12, 1984 Women Against Pit Closures organized an all-women rally and march through Barnsley and invited women’s support groups from all over the country to join them. The response was huge, and at least 10,000 women attended the rally. After Barnsley, another women’s rally in London was organized and took place on August 11, 1984. 15,000 women attended.

“We are sort of re-educating them slowly. They are not liking it a lot . . . But slowly they are coming round to it. They don’t call us ‘ladies’ any more. They call us women. That’s a start.” — Susan Petney from Blidworth, WAPC Member

Throughout the strike, WAPC groups organized soup kitchens, distributed food parcels, organized Christmas appeals for miners’ families, distributed Christmas cards, and produced all sorts of protest paraphernalia — postcards, calendars, badges, a book called We Are Women, We Are Strong, t-shirts, and banners. Women also actively joined picket lines, formed parts of flying pickets, were involved in confrontations with the police and travelled the country speaking at political meetings and the world explaining why miners were fighting for their jobs and communities with the hope of financial support.

Throughout the strike, WAPC groups organized soup kitchens, distributed food parcels, organized Christmas appeals for miners’ families, distributed Christmas cards, and produced all sorts of protest paraphernalia — postcards, calendars, badges, a book called We Are Women, We Are Strong, t-shirts, and banners. Women also actively joined picket lines, formed parts of flying pickets, were involved in confrontations with the police and travelled the country speaking at political meetings and the world explaining why miners were fighting for their jobs and communities with the hope of financial support.

Some men resisted when women became involved in the strike until they realized, if sometimes begrudgingly, how vital they were to its continuation. However, it wasn’t only men in the mining towns whose thinking was changed, the strike similarly transformed how women were perceived by the rest of the country.

“The comfy, media image of working class wives whose husbands are on strike has been one of them conservatively egging them back to work, stabbing them in the back. One by-product of the miners’ women’s action is the creation of a powerful new image, distinctive, feminist, and very much part of the 80s.”

Women were even able to take advantage of these societal expectations and could often easily move through police blockades on their way to flying pickets. Women, when stopped by the police, would pretend they were going to a “single parent conference” or “potato picking” or any other story they wanted to try and were waved through easily.

In many cases miners’ wives were switching roles with their husbands who were now taking care of the home while the women were going out and fighting against the strike. Some woman left unhappy marriages following the strike, some got a greater education, and some continued into politics. Anne Scargill, Arthur Scargill’s wife at the time, remarked cheerfully: “The whole experience made me harder and stronger.”

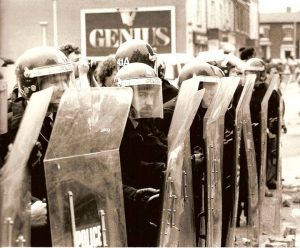

Violence

The strike was “as close as [Britain] came to civil war.” — Lee Hall

Over the course of the nearly year-long strike 11,291 people were arrested and 8,392 people were charged, mostly with rioting or unlawful assembly, houses were smashed up, dozens were injured, and a few people even lost their lives. David Wilkie, a taxi driver, died taking two scab miners to work at Merthyr Val Colliery when a concrete post was dropped from a bridge onto his car. At Bliston Glen Colliery in Scotland miners from the recently closed Polmais pit tried to stop others going into work and punches were thrown. In September thousands of miners and police clashed at Malty Colliery near Rotherham. In Nottinghamshire, 8,000 police officers were drafted to deal with flying pickets.

Over the course of the nearly year-long strike 11,291 people were arrested and 8,392 people were charged, mostly with rioting or unlawful assembly, houses were smashed up, dozens were injured, and a few people even lost their lives. David Wilkie, a taxi driver, died taking two scab miners to work at Merthyr Val Colliery when a concrete post was dropped from a bridge onto his car. At Bliston Glen Colliery in Scotland miners from the recently closed Polmais pit tried to stop others going into work and punches were thrown. In September thousands of miners and police clashed at Malty Colliery near Rotherham. In Nottinghamshire, 8,000 police officers were drafted to deal with flying pickets.

Flying pickets became common at pits where miners continued to work Organized groups of strikers around the country would travel to working mines to try to persuade working miners to join the strike. Nottinghamshire was a particular target. So that they could be at the pits before dawn, before the striking miners arrived, many police officers would leave their families on a Sunday to board a coach to temporary accommodations. Police officers would sleep in places such as town halls where they would live out of kitbags and sleep on the floor before returning home the following Friday.

The most notable confrontation between miners and police was the ‘Battle of Orgreave’ on June 18, 1984. Police in riot gear with police dogs and horses charged a largely peaceful crowd of miners on the picket line. At Orgreave, around 10,000 miners came to picket and faced off with around 5,000 police officers. However, the confrontation did not start violently. The police had their long shields, all their protective gear, batons and helmets on and miners ex changed remarks with the police and a few stones were thrown over. However, people were sitting or standing around in small groups and there wasn’t actually much going on. Many men had even taken their shirts off in the heat. That calm, however, quickly turned to havoc. In this chaos of the ‘Battle of Orgreave’ dozens of miners and officers were injured and nearly a hundred miners arrested.

“They marched me back down the hill to the line of police officers with shields and bounced me off them. The line opened up and they knocked ten bells of crap out of me.” — Stefan Wysocki, a miner arrested at Orgreave

“They marched me back down the hill to the line of police officers with shields and bounced me off them. The line opened up and they knocked ten bells of crap out of me.” — Stefan Wysocki, a miner arrested at Orgreave

Former police officers who were at Orgreave have admitted they were told to use as much force as possible and to charge at the largely peaceful crowd. They share that many officers were somewhat relishing the experience.

“The police were actually having a very good time, they were enjoying this huge exercise of brutal authority, so I found that very disturbing.” — Lesley Boulton

Strike’s End and Aftermath

“Easington . . . which was a very vibrant, strong, crime-free, well-educated working class community is now one of the black holes of European poverty” – Stephen Daldry

In November, a growing number of miners returned to work as Christmas approached and violence on the picket lines became more widespread. On March 3, 1985 delegates at an NUM conference decided 98 to 91 to end the strike. The miners lost the strike, going back to work without an agreement from the government after a year without work and without wages. After the failed strike, the NUM lost a lot of its power and influence and the mining industry was mostly destroyed.

In November, a growing number of miners returned to work as Christmas approached and violence on the picket lines became more widespread. On March 3, 1985 delegates at an NUM conference decided 98 to 91 to end the strike. The miners lost the strike, going back to work without an agreement from the government after a year without work and without wages. After the failed strike, the NUM lost a lot of its power and influence and the mining industry was mostly destroyed.

Following the strike, many miners felt degraded. Broken. They walked back to their pits with tears in their eyes waiting to find out if they still had jobs. Many former miners still viscerally recall the near-starvation, the police brutality, the lying media, the solidarity of the strikers,and the feeling of defeat but not humiliation. There’s a song sung at Anfield which illustrates just how deep the hurt continues to run in Liverpool when it comes to Margaret Thatcher. It’s called: “We’re going to have a party when Maggie Thatcher dies.

Margaret Thatcher. It’s called: “We’re going to have a party when Maggie Thatcher dies.

Many are still in no mood to offer forgiveness to Margaret Thatcher, the police, and to the scabs who they feel betrayed their union, communities, and way of life. Many miners felt that what the scabs didn’t understand is that the strike wasn’t about pay and conditions, it was for jobs and communities – they were trying to save a way of life and the scabs helped Thatcher destroy their jobs, their communities, their history, and their future.

“Once a scab, always a scab. I still feel the same way as I did then. They are non-people, they don’t exist. There’s the odd one or two I might talk to, but they are still pariahs. Reconciliation is not bloody likely.”

Now it is all but gone and in its place many communities were overrun by unemployment, drugs, crime, and desperation. Thatcher is still hated by many in Britain for the destruction of the NUM, the mining profession, and mining communities. In 1984, 170 collieries were working in the UK and employing more than 190,000 people and entire communities. Today centuries of coal mining in Britain has all but ended. Many former miners have since found new lines largely in less difficult and dangerous conditions. And though most don’t miss the conditions in the pit, they do still feel the loss of the close-knit community that the mines engendered.