The screenwriting partnership of Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett resulted in some of Hollywood’s landmark motion pictures: Ninotchka (1939), Ball of Fire (1941), The Major and the Minor (1942), Five Graves to Cairo (1943), The Lost Weekend (1945), A Foreign Affair (1948) to name just a few. From their unique vantage point they concocted the story of a fictional screen writer “Dan Gillis” who would be introduced to the audience as a corpse on a morgue gurney. Speaking telepathically to his fellow dead bodies, each describing the means in which they met their end, Dan, whose name would late be changed to “Dick” in rewrites, would regale us with his story of faded celluloid glamor, madness and murder. The vision was to be a damming Hollywood black comedy to star Mae West and Marlon Brando and, in an effort to keep studio censors off their trail, Wilder and Brackett gave early drafts of the script the innocuous title “A Can of Beans.”

The screenwriting partnership of Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett resulted in some of Hollywood’s landmark motion pictures: Ninotchka (1939), Ball of Fire (1941), The Major and the Minor (1942), Five Graves to Cairo (1943), The Lost Weekend (1945), A Foreign Affair (1948) to name just a few. From their unique vantage point they concocted the story of a fictional screen writer “Dan Gillis” who would be introduced to the audience as a corpse on a morgue gurney. Speaking telepathically to his fellow dead bodies, each describing the means in which they met their end, Dan, whose name would late be changed to “Dick” in rewrites, would regale us with his story of faded celluloid glamor, madness and murder. The vision was to be a damming Hollywood black comedy to star Mae West and Marlon Brando and, in an effort to keep studio censors off their trail, Wilder and Brackett gave early drafts of the script the innocuous title “A Can of Beans.”

Wilder and Brackett knew what they were writing, what it would expose and whom they might offend. 1949/50 was turning point in Hollywood. The conclusion of WWII revealed a population exposed to a world that did not resemble the “Andy Hardy” America Hollywood had long portrayed during the previous decade. The arrival of rock and roll, the evolution of film acting with The Actors Studio’s “method,” the beginning of the end of the “studio system” and the unmistakable threat of television all signaled a seismic change was about to hit the film industry not endured since the advent of the “talkie.” Even the old, crumbling “Hollywoodland” sign would be torn down in 1949 and replaced with the renovated and reduced “Hollywood” beacon before the end of 1950.

Many of the great stars of the silent era: Louise Brooks, Wallace Reid, Mary Miles Minter, Ramon Novarro, Vilma Banky and more were still alive. What had happened to them? What became of the first celluloid gods and goddesses after their kingdom turned its back on them. Masters of the art of silent acting, many were rejected because of their inability to act inclusive of their voices or because the sound of those voices betrayed their German, Russian or even New Jersey origins.

The character of “Norma Desmond” is a fictional composite inspired by several real-life faded silent-film stars, such as the reclusive existence of Mary Pickford, the mental disorders of Mae Murray and Clara Bow and the grotesque, and even predatory acting style of Norma Talmadge. Even her name is suggested to be a combination of actor Mabel Normand and her lover, director William Desmond Taylor, who was mysteriously gunned to death (Perhaps by Mabel herself?).

As the screenplay developed, Wilder realized that Mae West was not the right actor for the film that he would direct. She was never offered the role. A phone conversation with Pola Negri, star of Madame du Barry (1919) difficult to comprehend through her thick Polish accent, went nowhere and led Wilder to silent stars Norma Shearer, Greta Garbo and Mary Pickford, none of whom showed interest. Director George Cukor suggested Gloria Swanson who, at the peak of her career in 1925, was said to have received 10,000 fan letters in a single week, and from 1920 until the early 1930s, lived on Sunset Boulevard in an elaborate Italianate palace. Suffering a lackluster transition to sound films, she had relocated to New York and, in the 1940s, was developing a new career on the Broadway stage. She was intrigued by Wilder’s proposal and happily signed on.

As the screenplay developed, Wilder realized that Mae West was not the right actor for the film that he would direct. She was never offered the role. A phone conversation with Pola Negri, star of Madame du Barry (1919) difficult to comprehend through her thick Polish accent, went nowhere and led Wilder to silent stars Norma Shearer, Greta Garbo and Mary Pickford, none of whom showed interest. Director George Cukor suggested Gloria Swanson who, at the peak of her career in 1925, was said to have received 10,000 fan letters in a single week, and from 1920 until the early 1930s, lived on Sunset Boulevard in an elaborate Italianate palace. Suffering a lackluster transition to sound films, she had relocated to New York and, in the 1940s, was developing a new career on the Broadway stage. She was intrigued by Wilder’s proposal and happily signed on.

And what of the silent film directors, who foundered under the demands of scripted dialogue and the restrictions of cameras locked down in sound-proof booths? Harold Lloyd, Lois Weber, D.W. Griffith, Dorothy Arzner, Mack Sennett and more. One of the most storied and even notorious was Eric Von Stroheim. Legendary for sophisticated plots and nourish sexual and psychological undercurrents in his storytelling, he embraced the moniker “The Man You Love to Hate” which he exercised to grand results in the treatment of his crews and actors. Best remembered for his brilliant work in the out-of-control masterpiece production of Greed (1924,) he even directed Gloria Swanson in the disastrous Queen Kelly (1929,) a production that contributed to bringing an end to his career, leaving him to focus solely on his work as an actor. This included a memorable portrayal as Field Marshal Erwin Rommel in Five Graves to Cairo (1943) directed by Billy Wilder who did not forget the master director when looking to cast Norma Desmond’s former Svengali and first husband.

The role of the former “Dan” then “Dick” now renamed “Joe” Gillis was cast with Montgomery Clift. Having an affair at the time with a wealthy middle-aged former actress Libby Holman, he was scared the press would start prying into his own checkered background and quit the production weeks before filming was to start. William Holden, who burst onto the screen in Golden Boy (1939) suffered a floundering career through the 1940s with mediocre roles in mediocre films. His hunger as an actor for any leg up at Paramount Studios was not unsimilar to that of his character “Joe Gillis.”

Conversely, the confusion of resemblance between Gloria Swanson and “Norma Desmond” was one the actress was to endure the rest of her life. No crazed has-been, Swanson was a dependable and accomplished professional who survived the gift of a return to the public eye and she navigated the scourge of typecasting for the remainder of her career.

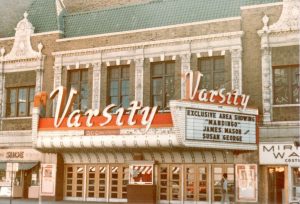

Following a disastrous first preview at the Varsity Theatre in Evanston, Illinois, where the audience howled through the first fifteen minutes of the film, Billy Wilder found himself confronted by a patron leaving the theatre who inquired as he sat on the lobby steps had he ever seen such a “load of shit?” He said he hadn’t. Upon his return to his editing room, he immediately proceeded to remove the scenes with Joe’s body in the morgue and begin the story where it starts as we know it, with Joe’s body floating, dead, in a swimming pool. From then on, it became the hit it remains today.

Following a disastrous first preview at the Varsity Theatre in Evanston, Illinois, where the audience howled through the first fifteen minutes of the film, Billy Wilder found himself confronted by a patron leaving the theatre who inquired as he sat on the lobby steps had he ever seen such a “load of shit?” He said he hadn’t. Upon his return to his editing room, he immediately proceeded to remove the scenes with Joe’s body in the morgue and begin the story where it starts as we know it, with Joe’s body floating, dead, in a swimming pool. From then on, it became the hit it remains today.

After a private screening for Hollywood dignitaries, Barbara Stanwick knelt in front of Gloria Swanson and kissed the hem of her skirt. The veteran actress particularly wanted to see what Mary Pickford felt and she was disappointed to see that Pickford had left right after the credits rolled. Swanson was told “She can’t show herself, Gloria, she’s too overcome. We all are.” M.G.M. Studios head Louis B. Mayer berated Wilder before the crowd of celebrities, saying, “You have disgraced the industry that made and fed you! You should be tarred and feathered and run out of Hollywood!” Upon hearing of Mayer’s slight, Wilder strode up to the mogul and retorted “Go f**k yourself.”

Recipient of three Academy Awards, Sunset Boulevard was presented on The Lux Radio Theatre Sep 17, 1951 with film stars Swanson, Holden and Nancy Olson and it was remade for television Dec 3, 1956 starring Mary Astor, Darren McGavin and Gloria DeHaven.

Gloria Swanson herself was the first to recognize its potential as a Broadway musical and, investing her own money, commissioned a stage adaptation to star herself entitled Starring Norma Desmond, later retitled Boulevard! It ended on a happier note than the film, with Norma allowing Joe to leave and pursue a happy ending with Betty. While it never got off the ground, video exists of her presenting a section of the musical for TV audiences on The Steve Allen Show.

In the early 1960s, Stephen Sondheim outlined a musical stage adaptation and went so far as to compose the first scene with librettist Burt Shevelove. A chance encounter with Billy Wilder at a cocktail party gave Sondheim the opportunity to introduce himself and ask the original film’s co-screenwriter and director his opinion of the project (which was to star Jeanette MacDonald). “You can’t write a musical about Sunset Boulevard,” Wilder responded, “it has to be an opera. After all, it’s about a dethroned queen”. Sondheim immediately aborted his plans. A few years later, when he was invited by Hal Prince to write the score for a film remake starring Angela Lansbury as a fading musical comedian rather than a silent film star, Sondheim declined, citing his conversation with Wilder.

When Andrew Lloyd Webber saw the film in the early 1970s, he was inspired to write what he pictured as the title song for a theatrical adaptation, fragments of which he instead incorporated into the 1971 film Gumshoe. In 1976, after a conversation with Hal Prince, who had the theatrical rights to Sunset Boulevard, Lloyd Webber wrote “an idea for the moment when Norma Desmond returns to Paramount Studios.” An early version of “With One Look”, then titled “Just One Glance”, was performed by Elaine Paige at Lloyd Webber’s 1991 wedding.

When Andrew Lloyd Webber saw the film in the early 1970s, he was inspired to write what he pictured as the title song for a theatrical adaptation, fragments of which he instead incorporated into the 1971 film Gumshoe. In 1976, after a conversation with Hal Prince, who had the theatrical rights to Sunset Boulevard, Lloyd Webber wrote “an idea for the moment when Norma Desmond returns to Paramount Studios.” An early version of “With One Look”, then titled “Just One Glance”, was performed by Elaine Paige at Lloyd Webber’s 1991 wedding.

With collaborators Don Black and Christopher Hampton, a complete performance was presented at the 1992 Sydmonton Festival with Patti LuPone playing “Norma” and Steppenwolf Theatre ensemble member Kevin Anderson as “Joe.” It was met with great success and began its way to Broadway via London and some casting choices that caused controversy on both sides of the Atlantic but that’s a whole different story!

Don’t miss Hollis Resnik in Sunset Boulevard

Don’t miss Hollis Resnik in Sunset Boulevard